The Clean Energy Mirage: Why MIT's New Investment Fix Won't Stop the Real Losers

MIT's push for better clean energy investment models hides a crucial truth: who is actually footing the bill for this supposed revolution?

Key Takeaways

- •Focus on financial optimization often masks dependency on government subsidies.

- •The real winners are large established players who can navigate complex regulatory capture.

- •Geopolitical supply chain risks are ignored by current financial modeling techniques.

- •The consumer ultimately pays for subsidized 'success' through higher, less flexible energy rates.

The Hook: Betting on Green, Losing on Reality

We are constantly told that the future is clean energy. We read reports—like the recent MIT analysis suggesting better financial models will unlock investment success—and nod along. But here is the unspoken truth: **clean energy investment** strategies are fundamentally flawed because they ignore the inherent structural risks baked into the transition. Everyone wants the PR win of funding renewables, but who is truly underwriting the volatility? This isn't about better spreadsheets; it’s about political will meeting hard economics.

The core finding from MIT points toward optimizing risk assessment and deployment strategies for novel technologies. This sounds great on paper. It means fewer spectacular flameouts of multi-billion dollar projects. But this focus on *optimization* distracts from the elephant in the room: the massive, guaranteed subsidy dependency that underpins most current **renewable energy technology** deployment. If the models are so good, why do they still require government backstops to compete against established fossil fuels?

The Meat: Optimization vs. Subsidization

The problem isn't the modeling; it's the market distortion. When institutions like MIT focus on making investments *more successful*, they are effectively perfecting the mechanism for extracting public funds. The winners here aren't necessarily the innovators; they are the established utility players and large infrastructure funds capable of navigating complex regulatory landscapes and securing long-term Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) often backed by sovereign guarantees.

Consider the supply chain. A focus purely on financial modeling overlooks the geopolitical fragility inherent in sourcing critical minerals. Are these new investment models factoring in the risk of a complete supply chain chokehold from dominant nations? Highly unlikely. They optimize for the known variables, ignoring the catastrophic, low-probability, high-impact geopolitical shocks that define true risk. This obsession with incremental financial success is a distraction from systemic vulnerability.

The Why It Matters: The Real Losers of the Green Gambit

The true losers in this optimization game are two-fold. First, the small-scale, truly disruptive startups that cannot afford the regulatory overhead or the decades-long PPA negotiation cycles. They get squeezed out by the 'too big to fail' green giants. Second, the consumer. Every optimized, subsidized investment eventually translates into higher rates for ratepayers who have no choice in their energy supplier. We are trading one form of centralized energy risk for another, repackaged with a virtuous narrative. This isn't about democratization of power; it's about re-centralization under a new banner.

Where Do We Go From Here? The Prediction

My prediction is that within five years, the regulatory environment will force a massive consolidation wave in the **green technology** sector. The current model of fragmented, heavily subsidized projects will prove too cumbersome and politically fragile. We will see private equity firms, having perfected the subsidy capture mechanism thanks to improved modeling, absorb smaller players. The result will be fewer, larger, 'too big to fail' clean energy utilities. This will paradoxically slow down true innovation while creating an even more entrenched energy oligopoly than the one we currently criticize.

We need radical decentralization, not better ways to manage centralized subsidies. Until that happens, MIT's findings are just sophisticated advice for securing the next round of government guarantees.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary risk MIT's new investment models aim to address?

The models aim to reduce the financial risk associated with deploying novel clean energy projects, specifically targeting better predictability in returns and deployment timelines.

Why is clean energy investment often considered structurally risky?

It is risky due to long lead times, reliance on fluctuating policy environments, high upfront capital costs, and often, dependence on government subsidies to compete with mature fossil fuel markets.

Who benefits most from improved clean energy investment strategies?

Large infrastructure funds and established utility companies benefit most, as they are best positioned to manage the regulatory hurdles and secure long-term, government-backed contracts necessary for large-scale deployment.

How does this relate to the overall energy transition?

Improved financial modeling accelerates deployment but may entrench existing power structures rather than fostering true market disruption or decentralization of energy production.

Related News

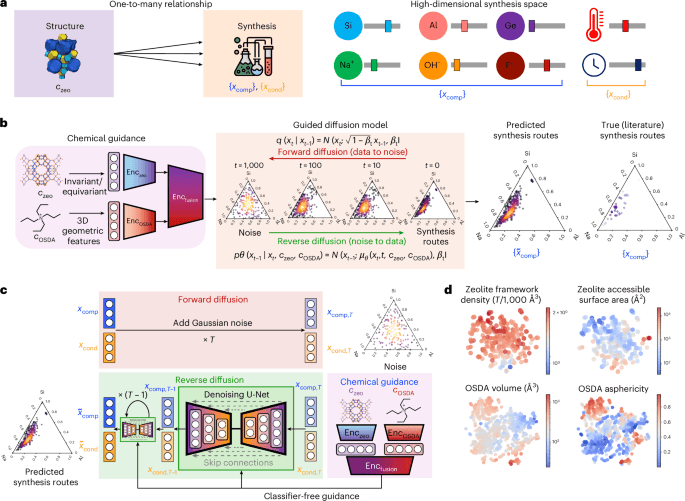

The AI Alchemy Revolution: Why DiffSyn Isn't Just New Science, It's a Threat to Traditional Chemistry Careers

Generative AI like DiffSyn is fundamentally reshaping materials science. Discover the unspoken winners and losers in this new era of chemical discovery.

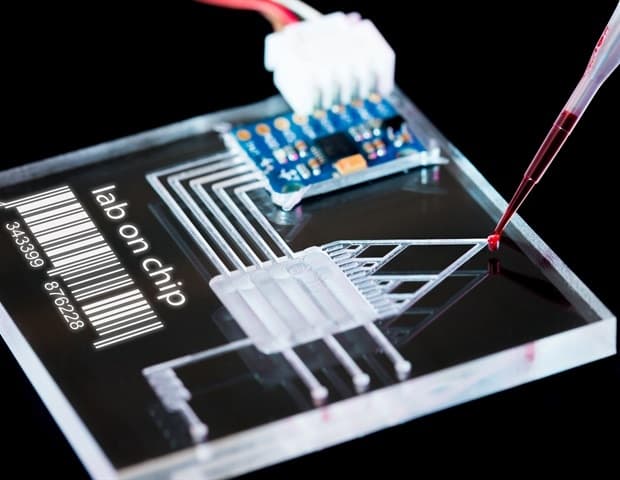

The Hidden Cost of Lab-Grown Organs: Why Simplified Microfluidics Will Bankrupt Traditional Biotech

Digital microfluidic technology is changing 3D cell culture, but the real story is the centralization of pharmaceutical power it enables.

The Hidden Cost of 'AI Saviors': Why Ravender Pal Singh's Math Background Exposes Silicon Valley's Shallow Hype Cycle

The journey from pure mathematics to AI innovation isn't just career progression; it's a warning about AI safety. Unpacking the real stakes.