The 97-Year-Old Slime That Exposes The Myth of Modern Science Speed

The world's oldest lab experiment isn't about physics; it's about institutional inertia. Discover who truly profits from this slow science.

Key Takeaways

- •The experiment's longevity is celebrated, but it represents institutional inertia rather than scientific necessity.

- •It serves as a safe, low-risk PR asset for the university, distracting from the need for riskier, high-impact research.

- •The future focus will shift from the physical experiment to the sociology of why it is maintained for a century.

- •The pace of 'slow science' is fundamentally at odds with the urgent scientific challenges of today.

The Unspoken Truth: Why The World's Longest Lab Experiment Is A Monument to Stagnation

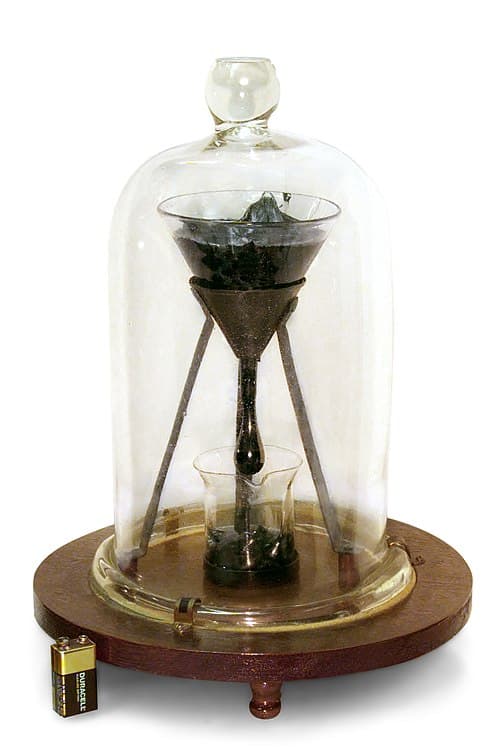

As the University of Queensland’s pitch drop experiment creeps toward its 100th birthday, the media celebrates a quaint scientific milestone. They laud the persistence required to watch tar-like pitch slowly, agonizingly, drip—perhaps once a decade. But this isn't a story about viscosity; it’s a damning indictment of modern scientific funding and publication speed. The real story of this longest-running lab experiment isn't the drip rate; it's the institutional victory of keeping a single, low-stakes project alive for nearly a century while groundbreaking research starves for capital.

We are obsessed with the viscosity of pitch, a substance whose practical application peaked before World War I. Why? Because it’s safe. It requires minimal funding, zero peer-review drama, and guarantees perpetual institutional relevance for the University of Queensland. This is the hidden agenda: slow science is reliable science for administrators. It’s a permanent fixture, a historical anchor that requires no disruptive innovation. While venture capital chases AI breakthroughs and gene editing, this experiment quietly consumes maintenance budgets, proving that sometimes, the most successful scientific endeavor is the one that changes absolutely nothing.

Analysis: The Illusion of Progress in 'Slow Science'

In an era defined by rapid iteration and the relentless pursuit of the 'next big thing,' the pitch drop experiment serves as a comforting, almost paternalistic, symbol of stability. But stability in fundamental science is often a euphemism for irrelevance. The key takeaway here, absent from most coverage, is the cultural trade-off. We laud this slow pace because it reassures us that science is methodical, steady, and controllable. Yet, this methodology actively discourages the high-risk, high-reward research that actually drives societal leaps. The longest-running lab experiment is a perfect PR piece: it generates consistent, low-effort content for decades, requiring minimal current intellectual heavy lifting.

Think about the resources—even minimal ones—dedicated to maintaining this setup versus what could be achieved by deploying those same resources toward solving complex, immediate challenges like fusion energy or antibiotic resistance. The underlying tension is between legacy funding models and the urgent demands of the 21st century. This experiment is a museum piece masquerading as active research.

What Happens Next? The Prediction of Perpetual Stagnation

My prediction is that the pitch drop experiment will continue indefinitely, but its *relevance* will pivot entirely from physics to sociology. Within the next five years, expect academic papers not on the pitch’s flow, but on the psychology of long-term scientific commitment. We will see theses analyzing the decision-making matrix that sustains it. The experiment itself will become less interesting than the *story* of why we refuse to let it die. Furthermore, I predict a major university will launch a deliberately counter-intuitive, hyper-accelerated experiment—perhaps using advanced rheometers and AI modeling—to achieve the same result in six months. The contrast will highlight the absurdity of the 100-year timeline.

The true disruption won't come from watching the drop; it will come from radically speeding up the observation process itself, exposing the ceremonial nature of the current setup. This fascinating look at viscosity is ultimately a mirror reflecting our own institutional fear of speed.

Gallery

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the pitch drop experiment measuring?

It is measuring the extreme viscosity of a sample of bitumen (pitch) at room temperature, demonstrating that pitch behaves as a fluid over geological timescales, not just a solid.

When did the longest-running lab experiment actually start?

The experiment began in 1927 at the University of Queensland, Australia, initiated by Professor Thomas Parnell.

How often does a drop actually fall?

Drops are incredibly rare. The first drop fell in 1938, the second in 1947, and subsequent drops have occurred every 8 to 13 years, with the most recent in 2014.

Is the experiment still relevant to modern physics?

While it provides empirical data on non-Newtonian fluid behavior, its primary relevance today is historical and as a demonstration tool, not as a source of cutting-edge discovery.

Related News

The 98-Year-Old Sticky Mess: Why Academia’s Longest Experiment Is a Monument to Obsolescence (And Who's Paying for It)

The world's longest-running lab experiment, the Pitch Drop, is nearing a century. But this slow science hides a dark secret about funding and relevance.

NASA’s February Sky Guide Is a Distraction: The Real Space Race is Happening in the Shadows

Forget Jupiter alignments. NASA’s February 2026 skywatching tips mask a deeper shift in space dominance and technological focus.

The Hidden Cost of 'Planned' Discovery: Why Science is Killing Serendipity (And Who Benefits)

Is modern, metric-driven science sacrificing accidental breakthroughs? The death of **scientific serendipity** impacts innovation and funding strategy.

DailyWorld Editorial

AI-Assisted, Human-Reviewed

Reviewed By

DailyWorld Editorial