Forget Human Migrations: The Secret 50,000-Year History of Island Hopping Pigs

The astonishing 50,000-year history of wild pig island hopping reveals a hidden force reshaping biodiversity and challenging our view of ancient maritime travel.

Key Takeaways

- •Pigs likely island-hopped across the Pacific for up to 50,000 years, indicating early, extensive human maritime activity.

- •This ancient dispersal acts as a blueprint for modern invasive species problems, highlighting the long-term ecological impact of early domestication.

- •The findings challenge current models of island colonization timelines, suggesting humans moved materials and animals earlier than previously confirmed.

- •Future research will likely focus on eDNA to track these ancient, human-assisted biological highways.

The Unspoken Truth: Pigs Weren't Just Flotsam, They Were Pioneers

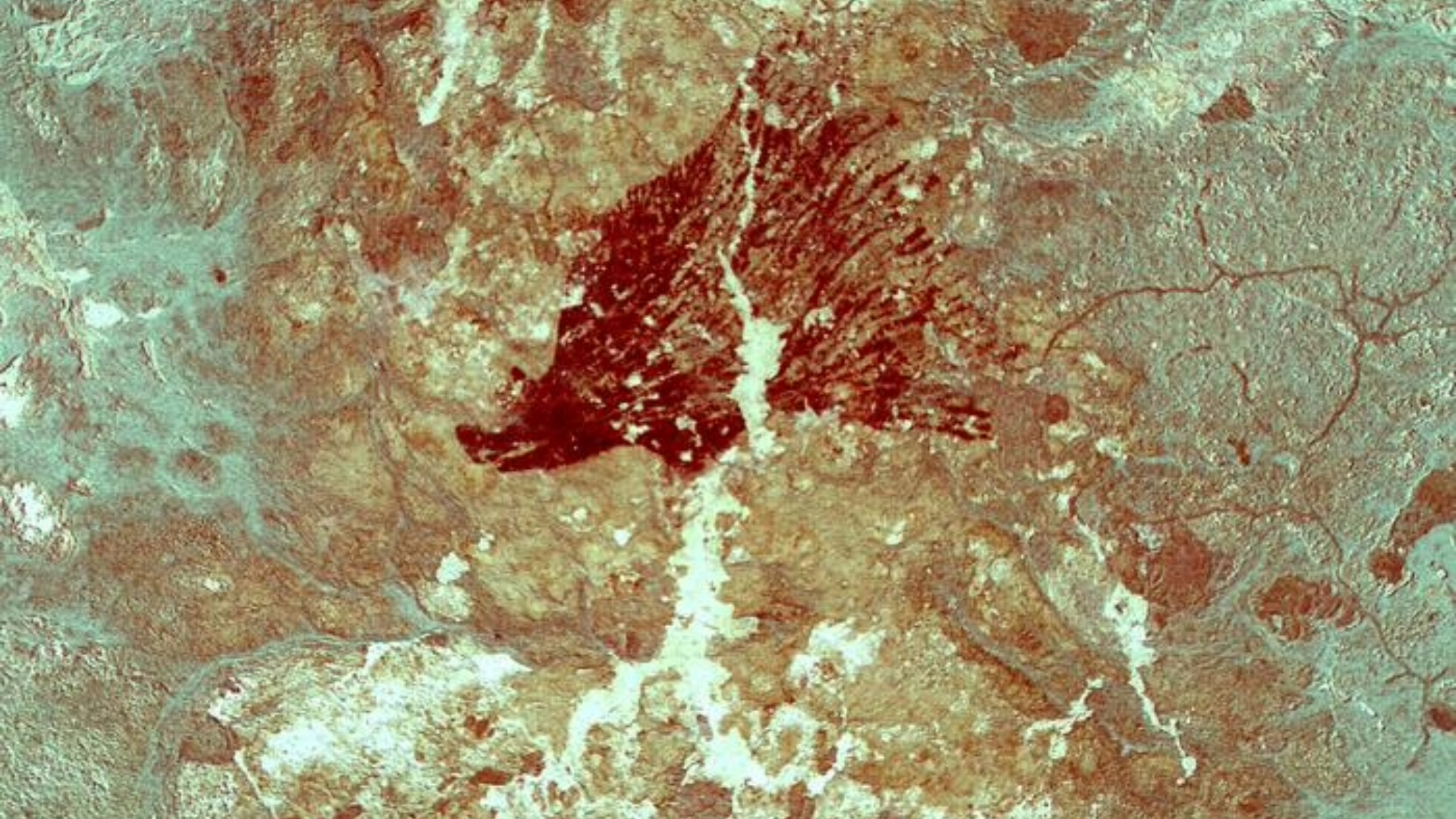

We obsess over human maritime history—the Polynesian navigators, the Phoenician traders. But while we were charting coastlines, a far more resilient, and frankly, more adaptable traveler was already mastering oceanic dispersal: the domestic pig (*Sus scrofa*). New genetic evidence suggests these seemingly ungainly animals have been successfully island hopping across vast stretches of the Pacific for potentially 50,000 years. This isn't just a cute biological footnote; it fundamentally changes how we view the movement of life, and crucially, the extent of ancient human influence. The core revelation, often buried under layers of academic jargon, is this: these successful long-distance voyages imply not just accidental rafting, but potentially **deliberate human transport** far earlier than previously assumed for certain island chains. If pigs, which are poor swimmers over long distances, made it, they were almost certainly passengers. This forces us to re-evaluate the timelines of early human coastal exploration and agricultural diffusion. The presence of these ancient pig lineages acts as a bio-marker for human activity across the ancient seas.The Real Winners and Losers in the Pig Diaspora

Who truly benefits from this deep history? The primary beneficiary is **evolutionary biology itself**, gaining a stunning case study in rapid adaptation. The losers? Our current, simplistic models of island biogeography. We tend to see islands as isolated laboratories. The pig diaspora proves they were, instead, interconnected hubs, even 50 millennia ago. Consider the economic angle. Modern feral pigs are ecological nightmares—invasive species that decimate native flora and fauna. This 50,000-year history is the blueprint for ecological disruption. Every modern conservation effort fighting invasive pigs is fighting a ghost of ancient human expansion. We are cleaning up messes initiated by our ancestors thousands of years ago, proving that the impact of early domestication was far more pervasive and immediate than the slow creep of agriculture suggested. Think about the implications for **invasive species management**—we are dealing with populations whose ancestors were professional globe-trotters.Where Do We Go From Here? The Prediction

Expect the focus to shift dramatically from *where* humans went to *what* humans brought with them. My prediction is that future archaeological and genetic studies, inspired by this pig data, will uncover even older, parallel dispersal events for other domesticated animals or specific strains of early crops, pushing back the established timelines of Pacific colonization by several millennia. Furthermore, expect increased funding for environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis in remote island sediments, searching for the genetic signatures of these ancient travelers to map out the forgotten super-highways of the Pleistocene. The pig is the Trojan Horse of prehistory. This isn't just about farm animals. It’s about understanding the true scale of **ancient human mobility** and the long, unintended environmental consequences of domestication. These island-hopping swine are the ultimate proof that human history and ecological history are inseparable.

Frequently Asked Questions

How could pigs swim or raft such long distances?

While pigs are poor long-distance swimmers, successful colonization implies they survived via 'rafting'—clinging to natural debris, logs, or rudimentary human crafts during storms or intentional transport by early seafarers.

Are the modern feral pigs on these islands related to the ancient population?

In many cases, yes. The genetic signatures found in ancient pig bones often link directly to modern feral populations, meaning current ecological challenges are rooted in prehistoric human activity, not just recent colonization.

What is the main significance of the 50,000-year timeline?

It suggests that the transfer of domesticated animals, a key marker of complex human societies, occurred across vast oceanic distances much earlier than previously established by archaeological evidence alone.

What does this imply about early human navigation skills?

It strongly suggests that the people accompanying these pigs possessed sophisticated, reliable navigation and sea-faring capabilities necessary to successfully transport livestock across open ocean, potentially thousands of years before established historical benchmarks.